14 May Stop the Violence

A still from Charm City shows a makeshift memorial for a young woman gunned down in Baltimore, which prompted her brother to vow to destroy his enemy — violence — by working harder to create peace.

During a panel discussion of a new PBS documentary, Charm City, about a collaborative community effort to take back Baltimore, LA County Assistant Public Defender Candis Glover spoke about the need to reach youths early on — before they enter the criminal justice system.

“We come across kids in the criminal justice system who are diagnosed for the first time with developmental disabilities or mental health conditions,” she told a large audience at the Promenade at the Howard Hughes Center in LA on May 1. “Why weren’t their issues addressed earlier?”

The event was organized by the Pan African Film & Arts Festival and PBS’ Independent Lens and also included panelists Skipp Townsend, cofounder of gang intervention nonprofit 2nd Call; Jasmyne Cannick, pop culture critic and race issues commentator; and Melina Abdullah, chair of Pan-African

Assistant Public Defender Candis Glover said that under no circumstances should a juvenile be treated and tried as an adult. Credit: Koi Kojer/Snap’N U Photos

Studies at California State University, Los Angeles, and a cofounder of the LA chapter of Black Lives Matter. CNN correspondent Nick Valencia moderated.

The documentary follows a diverse group of neighbors living amid a three-year stretch of violence in Baltimore and working toward healing their community. In addition to community activists, the group contained a police officer and government official, emphasizing the need to combine forces to lift up a troubled city.

The discussion explored topics from over-policing to treating violence in communities as a public health issue to mass incarceration of mostly black citizens.

Many pointed to gentrification as a primary reason people of color are kept in poverty, leading to crime.

Candis Glover speaks with, from left: Nick Valencia, Skipp Townsend, Jasmyne Cannick and Melina Abdullah. Credit: Koi Sojer/Snap’N U Photos

“We are being pushed out of our neighborhoods,” Cannick said. “We are being pushed out of our homes. Black people represent less than six percent of the people in this county but account for half of the people in jails. All of these issues are connected to having a home, having a community. Having that place where we can go.

“No matter where the crime and violence are happening, it usually does come back to gentrification and displacement.”

Townsend said that creating peace must be a youth-led movement. He pointed to a youth-led march for peace in early April in Crenshaw following the murder of community activist and rapper Nipsy Hussle. Gang leaders from Watts, Compton, L.A. and Inglewood all met up to discuss a cease-fire.

The subject turned to diverting young people of color from the juvenile justice system. Valencia asked Glover whether there was ever a reason that a juvenile should be treated and tried as an adult.

“No because kids’ brains don’t develop as quickly as you might hope,” Glover answered. “Kids, even into their 20s, still don’t have fully developed brains. So when you try to apply the same rules to a child as you apply to an adult and expect that child to understand consequences and how their actions can have a ripple effect, and you treat that child like an adult, you can’t have that expectation.”

Youths should not be sent to state prison as punishment, she said.

“I remember trying cases in Compton and sometimes even DAs would say, ‘I have this kid who has been transferred up from juvenile court into adult court and this kid is 15 years old. How am I going to send this kid to state prison?’ If you even have prosecutors who recognize that children cannot be treated like adults why is it that we continue to do this?”

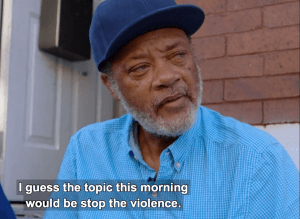

Featured in the documentary, Clayton “Mr. C” Guyton sparked a discussion about the role of patriarchs in urban communities with high crime rates.

In the documentary, one person featured was Clayton “Mr. C” Guyton, who in the heart of Baltimore’s Eastern District has earned the respect of local gang members, drug dealers and those just trying to survive in the neighborhood known as the “Middle East.” Mr. C and the Rose Street Community Center that he founded kept their four square-blocks free of homicides for 18 months. When Mr. C was hospitalized for a time, Rose Street saw a sudden uptick in violence.

Valencia asked whether part of the problem may be the perceived lack of patriarchs such as Mr. C in urban communities with high crime rates.

Glover said the issue was much more complicated.

“It’s a lack of a lot of things,” Glover said. “It’s making sure that the needs of children are addressed. If the kid is not going to school, there’s probably a reason that the kid’s not going to school. Maybe it’s because the kid has a learning disability or is hungry.

“So instead of pointing out the kid’s truant and now the juvenile justice system gets involved, and maybe the kid is taken out of their home, there has to be something more than just looking at the symptoms. We have to look at the underlying root problem.”

Panelist Melina Abdullah talks about personal responsibility, with Candis Glover. Credit: Koi Sojer/Snap’N U Photos

Some panelists predicted that gentrification would force out the African American population in LA County by at least a few percentage points in the next decade. They wondered if the African American prison population would remain as disproportional.

“I see a bleak future if you don’t do anything,” Abdullah told the audience. “But if you leave here and say ‘I don’t want it to go that way’ and you think about one thing that you can do and you do it every day and I mean every day, I think we can take the city back, take our power back and have peace in our community.”